We return from the Christmas break rested, full bellied and rosy cheeked (nothing like playing a half starved 18th century convict to kick start the new year detox). Following our initial groundwork we're ready to take our first plunge into getting the script 'up on it's feet'. This is the first exciting leap into the unknown - a chance to pour some of our discoveries from the last week into a more physical exploration.

Alastair explained that we would be working through the scenes of the play chronologically, and although the basic outline of the set was marked up in the rehearsal space, we were to stay very free and easy with any movement and not bog ourselves down with blocking at this stage. It should be more a chance to play with ideas, start making some decisions but certainly not setting anything in stone just yet. I always find there are so many things to consider when first standing up with the script; where your character has just come from, what's happened just prior to the scene, what your character wants, and what you are actively trying to do to others in the scene. It's nice to have the freedom to explore these things fully without immediately worrying about whether it's better to come on from stage left, whether you might be masking somebody or up-staging yourself!

|

| The art-work in our rehearsal room always gets us off to a cheerful start. |

Time-lines and titles.

Each scene in Our Country's good has a title. Some of which are useful pin-points ie. The First Rehearsal. Other titles Timberlake gives us are more Brechtian: The Women Learn their Lines, or more poetic and abstract: The Loneliness of Men. But one thing she does not give us is a specific time line. We know the play starts in "the hold of a convict ship bound for Australia, 1787". We know that in the second scene when the ship arrives it is "January 20th 1788". How much time passes between each scene from then on is not explicitly described. We are only told through Ralph's exasperation in the second act that "we have been rehearsing [The Recruiting Officer] for 5 months!" so it's up to the company to decide what time frame makes sense to us.

So before we start rehearsing each scene, we discuss how much time we think may have passed since the last scene; whether it's the following evening, a few days or even months later. It's important that we all have an idea of what's happened 'in-between' and how our relationships with each other have changed or developed.

The Voyage Out.

Approaching the above named scene, the very first scene in the play, has been tricky. Mary, Wisehammer and Arscott all speak about their experience on the ship, but it doesn't appear that they're having a conversation with each other, it's more a mediation on love, sex and hunger. But how do we approach this? No-one actually just speaks out loud to themselves for the sake of it, particularly in such a lyrical poetic manner. Who are they speaking to? What prompts them to speak? Is it the flogging of Sideway they've just witnessed, or something else? We discuss the idea that Wisehammer is perhaps composing aloud. He loves words after all - maybe this is his outlet for dealing with the horror he sees around him. And who is Mary talking to? I feel like although she would be surrounded by people she is somehow alone. Perhaps she's is praying, a confession, trying to explain herself to God. There's certainly still a lot of un-picking to do to work out how this evocative opening can be staged to fulfil it's full impact.

There's a wealth of books floating around the green room now, and as more of the cast read Max Stafford-Clark's rehearsal notes on the original Royal Court production (see his books Taking Stock and Letters to George) we're beginning to wonder if the printed version we are using was 100% proof or whether there were trimmings and additions that smooth over the bumps and explain the gaps. After all the play was not written in the traditional way, but rather devised from scratch with Max, Timberlake and a company of actors over a long series of workshops. Numerous drafts and redrafts were made and it seems that what was finally performed is unlikely to be what was exactly published. The publishers deadlines meant the printed version had already been made, despite re-writes continuing right into the first preview performance.

Something about Mary.

|

| The real Ralph Clark and his wife, Betsey Alicia. |

In Keneally's novel The Playmaker (which OCG is loosely based on but not a book which we by any means are using as the final word in character decisions) there is a brief description of Mary's childhood and upbringing. This has also informed my biog for Mary, although there were still lots of gaps to fill. This kind of exercise gives me a (possibly false!) sense of security that I know who this girl is in my mind, I know where she comes from, her family background and any major events that have happened to her up to the point at which we meet her in the play. I find it very useful to imagine what circumstances led Mary to this point her life (ie. being arrested and sentenced to transportation). I won't go into the details of my made up history for Mary - it's not something the audience watching would know about, and certainly not something I'd expect them to telepathically understand from my acting - it's really just useful tool for me.

I've been thinking a lot about a particular characteristic of Mary's. Compared to many of the other convicts she seems abnormally quiet. Through much of the first half of the play Mary very rarely speaks. In fact, one of the first times we hear her, the stage direction suggests she speaks "inaudibly". Until Mary finds her voice through acting, Dabby does most of the speaking for her and later in the play Wisehammer suggests hat she is shy. When she does speak, it's often in short, precise sentences. She's not one to procrastinate or elaborate.

But my job is not to simply label her as quiet or shy and try to act that, but to understand why she holds back or finds it difficult to speak. And more interestingly, I've been thinking perhaps Mary wasn't always like this. It's the horrendous experience on board, being pimped out to the sailor on ship, the abuse she has suffered that has caused her to retreat into her shell. It makes her journey far more exciting to me. The idea that Mary doesn't just find her voice and her confidence through performing and through Ralph, but that she allows herself to find her old self again. So when we see Mary at the end of the play, excited and opinionated about her part as Silva, able to speak up to Dabby, or bold enough to suggest that she should take centre stage for the convicts curtain call, perhaps we are seeing the real Mary. The one that until now, had been left behind in England.

Emily x

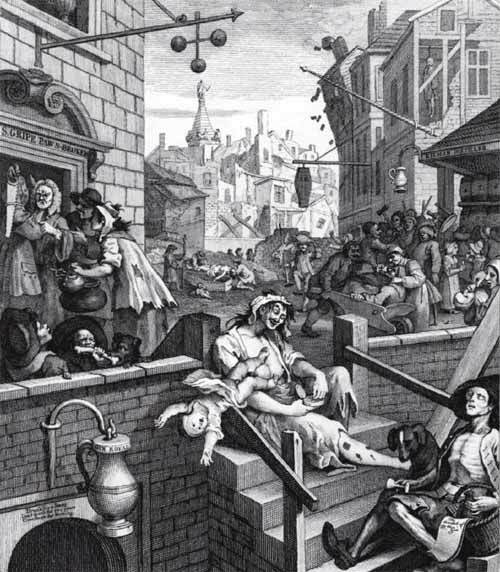

|

| Hogarth's paintings are so evocative of the period. This one is called Gin Lane (1750) |

No comments:

Post a Comment